Audio and Video, Drylands Management, Sunseed Stories

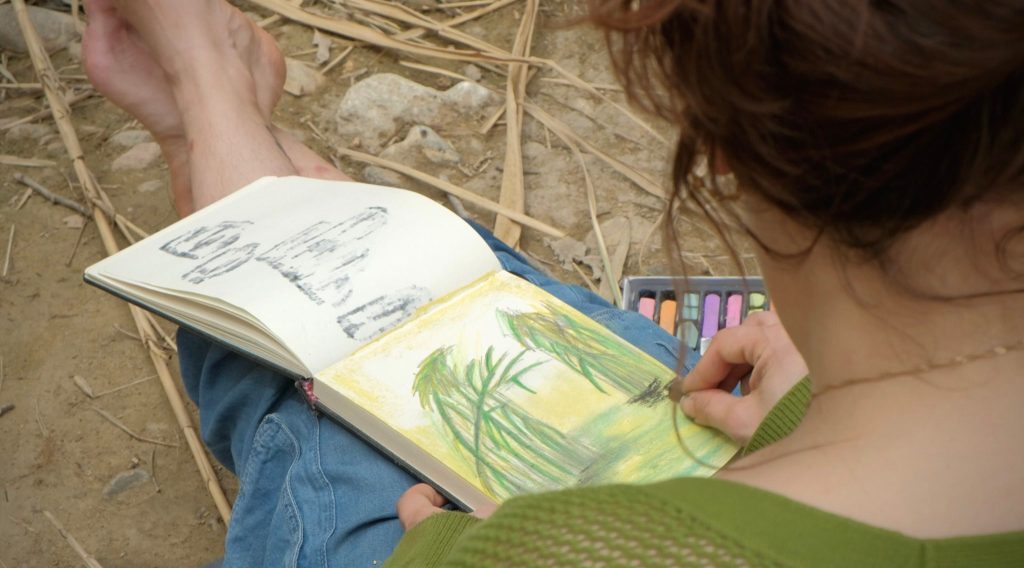

In this article, we want to share with you the artwork of Anouk, a former drylands assistant, that she made during her stay on the project and how, from her perspective of living in a community, the activities she did daily and the knowledge gave her more tools to make us more aware of nature and the importance of the poza (natural pond) that has so much meaning for Sunseed.Here is what she wrote about the concept of the video and her thoughts:

The video that I made is an experimental audio-visual piece that explores the ways in which we are in conversation with our environment. By experimenting with alternative filmmaking methods, I aim to capture the more-than-human experience of the surrounding drylands of Sunseed in order to expand and disorient our human gaze. The name of the piece, ‘Can I See Through You’, signifies the question that guided me through this process. The ‘You’ in the title is referring to all the nonhuman elements in the environment you can imagine, think of the ants, the gypsum, the clouds (or the lack of them), the trees and even the spirits.

You might wonder why putting all this effort in empathizing with rocks and insects and trying to capture their perspective is of any value. In the end the video that I made consists of vague images and dubious sounds without a clear message to take away from it. Nevertheless, I think there is real value in expanding and disorienting our human perspective. One of the root causes of why we are facing a multifaced climate crisis, is fundamentally that at some point in history we have come to see ourselves as something separate from and even superior to the rest of nature. Most filmmaking methods represent this anthropocentric approach. When the climate crisis is portrayed in film, it is often done with the use of dramatic storylines, a narrator whom we can sympathize with and some experts who present some factual information. Moving away from this human perspective and using other filmmaking methods that focus on imagining what life must be like from the more-than-human perspective, gives us the chance to attune to nonhuman lifeworld’s. This opens up our understanding to the rather slow form of violence that is induced by destructive human activities. The damage that is being done to our planet is a slow kind of violence because much of it occurs indirectly, gradually and out of sight.

The video is meant to be projected on the rocks next to the poza, partially in order to connect the recorded footage with the present moment, but especially for the purpose of enhancing the sense of disorientation of our human perspective on this world. It might bother you to not exactly understand what you are seeing, or you might get curious about what the video actually looks like, but this confusion or discomfort is entirely the purpose of the experience. I believe that film is capable of producing knowledge, not just representing it. So with this video I’m not so much putting forward a certain vision or idea. The aim is to create an experience, in which you can make your own interpretations, come up with your own questions and draw your own conclusions.

This part I recommend you to read only after you’ve seen the video, so you can watch it unbiased and make your own interpretations.

There are two main ideas I worked with in this video. The first part of the video is inspired by a talk I heard in which someone explained how in pre-literate times, we saw the human mind not as anything different than a streaming river or the changing weather. Constant change, appearing and disappearing. I very much liked this idea, to realize that also the thoughts we have are natural phenomena. The gibberish whispers represent thoughts, of which rather often the content is quite unimportant, yet they can be overwhelmingly loud. But then the whispers quiet down. After our minds have wandered in all directions, finally it becomes silent and that is the moment that we can tune into our environment. The breathing, the sounds of the environment and the visuals are harmonized. I came to this idea mostly because I had a ridiculous amount of zooming footage and I was trying to figure out what to do with this. At some point I made the connection between the zooming and the breathing. Then I realized that breathing together with the environment, sonically and visually, was very much in line with this idea of attuning with the nonhuman experience.

This short video was made in a very short time-span and is just one experimentation of how you might capture the more-than-human experience. But the entire process of making the video might actually be the most interesting part. So I would encourage anyone to pick up a camara, you’re phone will do perfectly too, make some sound recordings, try to attune to your environment and see what you come up with.

If you’re interested in experimental filmmaking methods that aim to capture the more-than-human experiences, you can check out Isabelle M. Carbonell’s PhD dissertation. It’s a long read which I still by far haven’t finished, but has fascinated and inspired me completely. You can find it on the internet when you look for: Isabelle M. Carbonell Attuning to the Pluriverse.

We hope you enjoyed the reading. Leave us your comments on what you think about the video.